THERE . . .

. . . A warm, moist nudge of a nose on a dangling bare ankle interrupted my suffering stupor. It was a cold gray day in late October 2010 and Bailey, my blond, soft furry spaniel mix wanted attention—as usual.

I was perched on a high-back chair leaning over the kitchen counter with my face in my hands trying to figure out what to do or not do. Trying not to cry or scream. Trying to hold my racing thoughts, pounding heart and bound up breath inside a body that threatened to explode or implode. I could never tell which.

I was in severe pain—eight out of ten—as usual.

“How did I get here? How did this happen to me? WHY did this happen to me?”

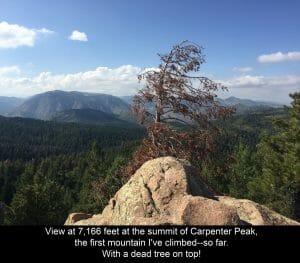

A year ago, I was bounding out of bed at 5 am to go to boot camp workouts before heading to work at the hospital. I was fit, happy, and planning on climbing a mountain next summer—and not just any mountain, a great big 12-14,000 foot one in the western Colorado sky that dared me, at 50 years old, to think I could.

But now, at 51, I couldn’t even get groceries without being in bed for two days afterwards. My flower gardens were full of dried brown weeds and the dust on the top of my refrigerator had turned into

Like me, they struggled with trying to figure out what to do or not do. I was having difficulty coping and was struggling to maintain a sense of purpose in life.

The pain was perplexing to all of us. Friends, family, and health professionals were all baffled, and even the kid bagging my groceries looked confused when I asked for help loading my car. I didn’t look sick, hurt or disabled. Nobody understood or could tell me why I hurt so bad . . .

. . . HERE

I walked three miles today, in the sunshine, up and down the Colorado hills behind my house as fast as I could with Gloria Gaynor belting “I Will Survive” and Sara Bareilles encouraging me with “Brave.”

It’s been nine years this week since I was first injured on the job, eight years since the day I sat with my head in my hands wondering if life as I had known it was over. It was the day my health providers “gave up” and told me I was doomed to live the rest of my life in constant, debilitating pain.

Despite trying not to cry or scream that day— I did both. Then I got mad because they were wrong, all wrong. Wrong about the way they had been treating me, wrong about what was going on in my body, wrong about it “being all in my head,” and wrong that I would always be in pain.

Until I was judged “hopeless” and given a life sentence of pain, I believed therapy and treatments would eventually “fix” me—if I just did everything I was told to do. Except it didn’t work. But “hopeless” had never been a belief word in my vocabulary as a healthcare provider, or as a human being.

I believed in healing and had lived my entire career and life from a foundational belief in the power and ability of humans to overcome. “Hopeless” was an identity I could not accept for myself. Not then, not now, not ever.

How I got from there to here

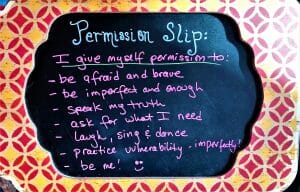

First, I jerked the pen and the story of my life out of the hands of others and started writing myself “permission slips” to be the boss of my own life, my own feelings, and my own healing.

What are permission slips? In younger years, permission slips were signed by my parents so I could go on a school field trip, or by the teacher so I could leave the classroom to go to the bathroom. Without these permissions I couldn’t do things or go places, so permission slips held power over my freedoms—to act and be in the world.

Whoever writes them is the holder of that power, and as a pain patient I realized I had surrendered that power to prescription writers and therapists. So, I started shifting my role with healthcare providers from “patient,” with little power and influence, to “the boss”— “I give myself permission to be the one in charge.”

Taking charge didn’t mean I was blaming, arguing, or trying to power wrestle with other people, it meant being able to speak up for what I really needed.

Many other “permissions” followed—to say no if I needed to say no, to speak my story and my truth, to challenge false judgments or diagnoses, to make my own decisions, to feel my feelings without

I also gave myself permission to be brave and afraid (at the same time) in order to relentlessly pursue my own recovery through all the ups and downs and good and bad days that were still to come. I accepted that such challenges would be a part of living with pain, but that didn’t mean I couldn’t live well, so long as I gave myself permission to do so.

Over time—a few years in fact—the pain and perplexity gradually yielded to a calmer sense of ownership of my body, my story, my emotions, and my choices in life. I learned skills that I still practice today: self-compassion, self-direction, self-care, self-kindness, self-trust . . . the list goes on.

When I’m asked about how I recovered from debilitating pain to being suffering-free and joy-full today I have to share that I still have my injuries—five of them, to be exact. Two from the original work injury, and three treatment injuries to other parts of my body—one of which became my persistent pain injury. So, I’m not “fixed” by any means. I never expected to be pain-free, I just wanted to be able to live a happier, more meaningful life.

Now, when I sit with the people in chronic pain I try to support, I ask them what I’ll also ask you:

“What permission slips do you need to write today—to start moving from here to the “there” you want?”

Linda Crawford was a live-by-the-rules black, brown, and boring shoe wearing girl for most of her life, except when earning trophies in her younger years as an off-road professional rally car co-driver. At the age of fifty a work injury led to four years of debilitating persistent pain, and it was during that difficult time that Linda finally developed the courage to wear red shoes and to experience life as beautiful—even when it seems the darkest and most colorless.

As an occupational therapist and certified facilitator of Brené Brown’s Daring Way™ and Rising Strong™ curricula, Linda hopes to help people in pain to discover the beauty and color in their own lives while they endeavor to restore their bodies, rebuild their lives, and renew their joy.

Connect with Linda through her private practice in Denver, Colorado—Brave Pain Therapy—at Bravetherapy.net, Braving pain.com, or bravepaintherapy@gmail.com.

Worried about back pain? Rule out these 8 “red flags” first

Worried about back pain? Rule out these 8 “red flags” first