Getting to Know Your Nervous System

Most people have some sense of what the human skeleton looks like, but what about the nervous system?

It’s a wonderful web of nerve

This post is number 2 in the series from physiotherapist Diane Jacobs. She explains the nervous system and the role it plays in pain, just as she does when she sees people in the clinic. She’s talking to Alex, a man who’s had a fall from his bike and has been struggling with ongoing neck pain for two years.

Assessing Movement Quality

I take a look at Alex’s range of movement before I ever touch him.

I’m interested more in how he moves rather than how far he can move, quality not quantity. To respect someone’s body, and treat it kindly, it’s important to have a sense of their sensitivity and confidence to move.

I’m also interested in how Alex inhabits his body and in particular how he expresses himself through his neck and head. It tells me a lot about what he is feeling. I’m not a therapist who reads much into posture or tries to make people’s motion more symmetrical between sides. I am way more interested in the symmetry of their movement behaviors, their motor output when they are not moving, and what I like to call “default resting behaviors.” All of these determine the kinds of stresses and strains that happen to someone’s body on a regular basis (read more about this at the end of the post).

Understanding your Nerves and why they Hurt

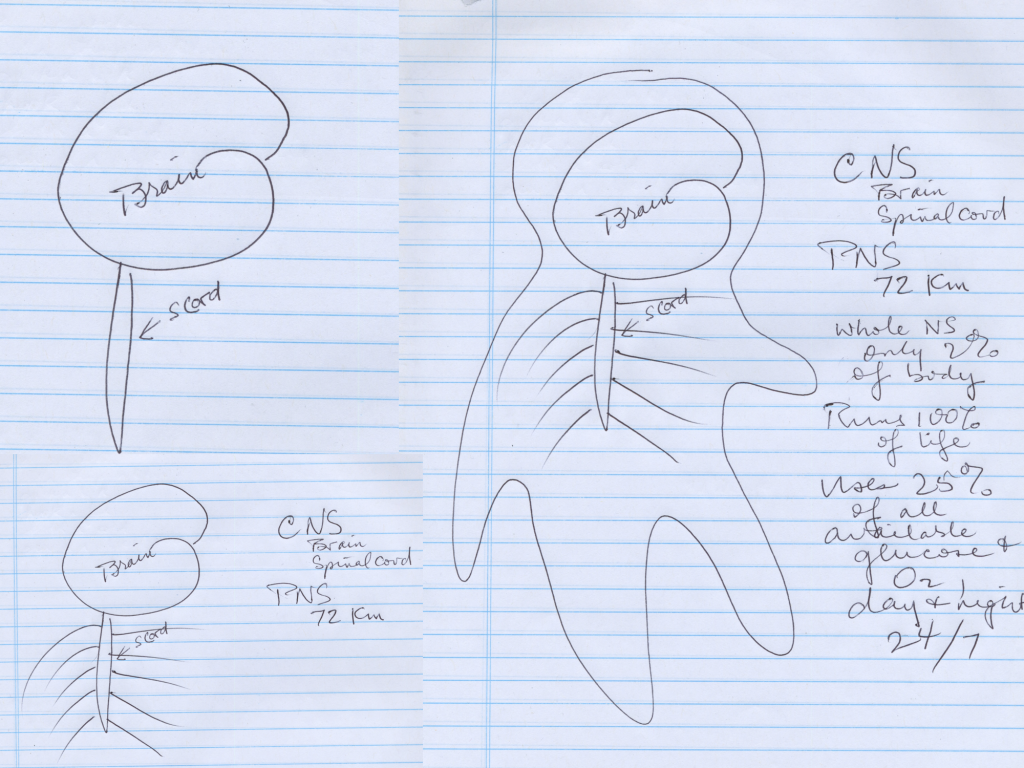

I sit next to Alex, and draw crude little pictures to explain the nervous system.

“Here is your brain and spinal

Diane explains:

“Picture a big three-dimensional net in your body made of nerves. The whole thing – brain, spinal cord, and nerve net – is only about 2% of the whole body, but it keeps us alive! We are part of it, rather than it being part of us, the way we usually think of one of our body parts.”

“This nervous system is the boss of us – it decides when it’s time for us to go to sleep and to wake up. All night long it keeps our heart beating and our lungs breathing. It wakes us up in the morning because it wants us to empty its bladder and then get it some coffee. It’s 100% responsible for all our functioning as humans moving along through life. To do all that it requires about 25% of all the glucose and oxygen available any moment of the day or night, 24/7. We ended up with a brain 5 times bigger than most other creatures our size, so you can imagine how much more fuel our nervous system requires to work properly.”

Alex appears interested, if still a bit bewildered.

“Nerves go everywhere in the body, including into your neck. They are responsible for telling muscles what to do and for reporting back to the CNS about everything going on in the body. Most of the time this all goes on without us being aware of it.”

Nerve Plumbing Problems

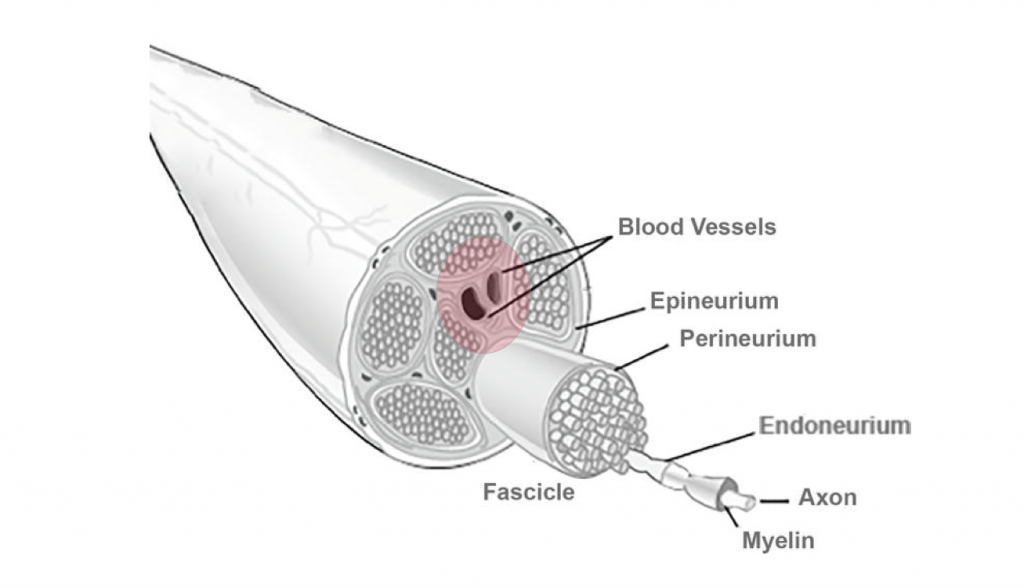

I show Alex a couple of Lundborg’s pictures of a nerve, enlarged, and explain how the nerve’s blood supply can be affected if it gets squashed.

“Now, picture that nerve net is connected with another net, the blood vessel net, all the way along its length and width. Sometimes there is a pull against this system, pulling it diagonally or sideways, putting a shearing force into it. Usually there isn’t much problem getting blood into a nerve, because you have blood pressure working for you, but drainage is a different story. If a nerve gets backed up with blood that is low in oxygen and no longer useful, a signaling system built right inside the nerve may report a problem either mechanical or chemical to the central nervous system. In fact, often what feels like a big pain turns out to have just been a plumbing problem inside some branch of some nerve. Because nerves are so important, this can create and send a big noise to the central nervous system.”

I give Alex a finger trap to play with so he can get the idea of how a nerve might feel if it’s under tension. He nods.

Then, I explain how the spinal cord might be contributing to tension, adding to the problem under the radar.

“The spinal cord came along first and our big brain came along a lot later. We still have a spinal cord that hasn’t changed much from the original design in less sophisticated animals than humans. It is very protective – if you accidentally touch a hot stove your spinal cord will take over your muscles and you will have pulled your hand away before you even realize the stove was hot. This efficient protection is why we still have this primitive system – nature never gets rid of anything that proves useful for survival – it just adds to it. In our case, it added a big brain to allow for more complex behavior beyond that generated by the spinal cord. The brain can also inhibit a lot of signals coming from the spinal cord, including danger messages routed from the body through the spinal cord.”

“Sometimes instead of inhibiting these messages, the brain allows the spinal cord and the older threat detection system to amplify the signal. And part of the way the spinal cord and the older parts of the brain do that is by creating tension in certain areas.”

“So, sometimes things can become glitched right inside the system, like an operating system problem that needs a reboot. Except a computer analogy only can go so far. I propose we consider your nervous system acting as though it were a frightened, cornered animal that is biting you on the inside of yourself and we want it to stop that behavior. We need to observe it, be careful and kind and give it options. We need to give the nervous system what it what it needs so it can change. Again, we come back to thinking about how kindness helps things change.”

“Usually, long term, all your nervous system needs is oxygen and glucose, provided with some attention and movement by you at regularly spaced intervals for 3 or 4 days. Motion is lotion is a good way to think of the way that moving more helps to keep our body nicely lubricated and all of the tissues well nourished. While I’m on the outside of you examining your neck, I’m working to try to drain the nerves in your neck and feed them with fresh, oxygenated blood. I do so carefully, without aggravating the nerves or hurting you more. You will be on the inside, feeling whatever is happening. If we work together we might be able to get your brain to change its mind. We will work on some movement homework too.”

Everyday Positions that can Cause Pain

There are many physical things people do, completely unconsciously, that can put twisting and compressing forces into their nerve net. Too much of this can have a negative effect by continuously irritating a part of the nervous system and starving it of blood, oxygen and glucose. Over time, this can take a toll and keep a sensitive nervous system from returning to normal.

I want to know how Alex sits to relax, and get specific details about how he does that.

- Is he is a leg or ankle crosser? If so, which leg?

- Where is his TV set located relative to his favorite chair?

- Does he have to turn his head to watch the TV?

- Does he lean on one elbow most of the time and if so, which one?

- Does he sleeps only on one side, if so, which side?

- How does he tilt his head when he listens?

- Which eye is his dominant eye? People will tend to try to put their dominant eye forward, a behavior which will automatically tense their neck a certain way all day long.

Alex and I sort through some of these typical daily postural or movement habits. He gradually gets the idea that there are likely lots of things he can observe about himself in his daily life and work towards changing if he so chooses. The change starts by simply becoming aware of them. I get lots of ideas about what sort of home exercise program I might suggest, if he seems to need something explicit assigned.

Then it’s time to ask Alex if he’d be comfortable if we do some hands-on manual therapy. Alex says he’s willing to give it a go. Find out how I integrate manual therapy into my approach to educating patients about the nervous system in the next post of this series on treating pain with kindness.

Diane Jacobs has been a physical therapist since 1970, and has used manual therapy to treat people with pain problems since the 80’s in her solo practice. In 2005 she helped to found the Canadian Physiotherapy Association’s Pain Science Division (PSD) and served on it until 2014.

In 2016 Diane published DermoNeuroModulating, a book which combines pain science awareness, clinical reasoning, and manual therapy strategies for pain. In addition to teaching workshops internationally, she owns and operates Sensible Solutions Physiotherapy in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, Canada, and is active online.

Your Back Pain Questions, Answered Part III

Your Back Pain Questions, Answered Part III