If you have ongoing pain, have you noticed how the intensity of your pain can change from day to day? Your actions, environment, thoughts, beliefs, body signals and the people around you have a big impact on your feelings of pain.

Health care practitioners often ask you when your pain is the worst, so they can pay special attention to medical problems. Switching that question around to “when do you feel the best?” can give you some important clues about the kinds of distractions that can work well for you.

You can use positive distractions and engaging activities to change what you’re feeling in your body. If that makes sense to you, and you’re confident to try new activities, even while you have some pain, you don’t need to read anymore. If you would like to know “why”, keep reading!

Pain Wants Your Attention

Pain is a life-saver because it’s hard to ignore. Pain is a very strong signal for you to take action and do something to make yourself safe again.

If your pain is caused by an injury or illness, seeking safety involve visiting a health professional to get your pain checked out. You might notice how you feel a bit better after making the appointment since you’ve taken a positive step towards getting help and finding the cause of the pain.

It’s trickier to understand your pain in conditions like persisting low back pain.

We now know that persisting pain conditions are not caused by injuries that haven’t healed. Usually, pain isn’t caused by the normal age-related changes happen in your body, even when those changes show up on scans and medical imaging.

Research shows that persisting pain conditions are caused by changes to the “alarm system” that works to keep you alive and out of danger. These changes lead your protective systems to generate pain in order to alert you to things that are not actually harmful or threatening to your body.

Pain is Protecting You, Not Attacking You

How can you make sense of pain that interrupts your life and keeps you from doing the things you enjoy, when that information isn’t accurately telling you about damage to your tissues?

Pain that’s always there can feel like it’s an enemy, relentlessly attacking you – but the truth is that pain is there to protect you from harm. In the modern world that we live in, signals that can be recognised by your brain as harmful are very different to just physical damage to your body tissues.

This video from Tame the Beast gives you a good explanation of what happens when your “protector” systems get out of control:

How is Your Pain Protecting You?

Your body is constantly receiving information from your surroundings. You are gathering far more information than you consciously know about – and all of it is important to keep you alive and well.

Sensors all over your body are collecting different kinds of information. They are part of your skin, in different organs, and inside your cells, blood vessels and nerves. They are everywhere, because your brain needs to know if you are in danger from the world around you, or if there is illness or imbalance on the inside of your body.

These sensors watch out for changes inside and outside your body that could be harmful to you. If there’s enough activity in those sensors to signal your brain about what they are detecting, then your brain has to decide what actions to take to keep you safe.

Actual or Potential Dangers

The sensors in your skin can detect pressure, stretch, chemical changes and heat. If something is stimulating them enough, they will send signals to your spinal cord, and then to your brain to alert it to changes in your body or environment.

These sensors are “danger detectors”, not “pain sensors”. The information from these detectors reaches many different locations in your brain. There’s not one “pain center” that gets activated like a light bulb, but rather many areas that are involved in processing the information coming in, and determining what action you need to take in response.

Pain is a complex experience, and the way that signals engage many areas of your brain make it look more like a lit-up Christmas tree, or a map of airport connections going in many different directions.

All of these brain regions act in a co-ordinated way to make a complex decision about whether you’re actually at risk of harm. Your sensors can’t make decisions about whether the stimulus is dangerous to you, they can only send messages. In addition to information from these sensors, your brain needs inputs from other sources like your vision, hearing, and memory of previous experiences.

If, given all of this information, your brain decides that there is a danger and you need to take action, you’ll feel pain. The purpose of the pain is to get your attention and take the appropriate action to protect your body from harm.

When pain is working as it should, your protective systems become more effective and responsive if you face a similar danger again. You stay alive by learning to adapt and to predict danger to yourself – and protect yourself.

The creation of easy-to-activate groups of neurons that fire together – called a “neurotag” – means that the next time you’re in a similar situation that activates the same pattern of neurons in your brain, you can quickly get a signal to protect yourself.

It’s a useful system to have in an environment where you have a lot of physical dangers to be aware of, because it allows protective responses, like pain, to be created fast and reliably.

If you live with persisting pain, you may not face a lot of physical dangers, but your nervous system continues to act as though it does. Your well-connected and efficient nervous system continues to create pain that stops you from enjoying activities and living a full life.

The Danger-Safety Balance

The efficient systems of brain activity described above are short cuts to fast actions in your body. The actions, or outputs, of the brain will depend on your brain’s decision about whether you’re safe or not.

A decision that there is danger will result in protective outputs from your brain – pain is the big one, but also changes to muscle tension, feelings of stiffness, swelling, fatigue and worry. These protective outputs alert you to slow down, stop, and pay attention to what is hurting or potentially causing harm to your body.

A safety decision has the opposite effects to a danger decision. Instead of protective outputs, your brain will release hormones and chemicals that dampen down the signals coming from your sensors, so you are less likely to feel pain.

Those times when you have less pain is when your “safety” is greater than your “danger” – and recognizing those times is a powerful tool for you to self-manage your persisting pain.

When Do You Have Least Pain?

Have you ever had an experience where you’re watching your favorite funny movie or sitting down with your best friend in deep conversation, and you notice that you don’t have pain, even if you’ve been sitting longer than you usually would be able to do?

That moment of realization is usually when your pain returns, as you fire up your protective neurotags when your realize you’ve been sitting for a lot longer than usual.

Some people who have persisting pain find that they experience a lot of pain in everyday tasks at home or work, but they don’t have symptoms when they do something risky and out of the ordinary like ride their bike, hit the ski slopes or have a night out dancing.

There’s an important lesson here about the power of motivation and doing things that are meaningful to you. When you’re doing something that really matters to you, you’re using a different pattern of brain activation, and not activating your pain patterns.

If you greatly exceed your usual activity, you might find you “pay for it” later, but these activities show you there are ways to sneak around your tolerance levels by doing things that you enjoy.

The Power of Distraction

Distraction is not pushing through your pain because someone told you to, while having that feeling in the back of your mind that you are doing something wrong or ignoring your body. If you do that you’re still firing up your danger circuits, and that’s not helping at all. Remember, the protective systems underlying pain are actually strengthened when you activate them!

Respecting your pain, rather than fearing it, is the key to moving forward.

Instead of ignoring pain, your aim is to find activities that are meaningful, engaging, and interesting to you. These activate your safety neurotags and tone down your danger neurotags.

You’re looking for ways to make your activity more important than feeling pain, so the things that matter will be unique to you. You can think back to things that you enjoyed doing before your pain started, or times, when you have noticed your pain, is reduced more recently, to give you clues about the best activities for you to change the way your brain is firing.

Not only is it safe to use these pleasure promoting distractions when you have ongoing pain, but it’s the fastest path to reset the sensitivity of your protective systems.

Distractions that increase the brain patterns associated with safety can gradually show you that it is possible to change your experience of your environment, your body and pain. You can start to combine things that are positive and distracting with activities that usually cause pain.

Here’s some ideas to get you started:

- Try art, craft or music practice that uses your hands and your mind, while increasing the time that you can sit or stand.

- Combine physical activity with something that distracts or interests you like walking and talking with a friend, walking and playing with your dog, listening to your favourite music or an interesting podcast while going for a stroll or dancing around the house to songs with good vibes.

- Do something with a sense of achievement and celebrate small wins when you do something like working in your garden, playing with your kids, cooking a meal or walking one street further than you did yesterday.

- Use specific “brain changing” activities like laughter yoga, meditation, visualization practices or brain training games.

- Watching a funny movie or listening to a funny audiobook while you’re exercising in the gym to stimulate the release of more “feel good” chemicals (don’t watch videos if you’re walking on the pavement!)

- If you’ve got to keep doing something, like getting home after a walk that is a longer distance, consciously make your brain work in a different way. Try counting forwards or backwards, counting up or down by three or by seven, saying the alphabet backwards or all the animals, names or places that start with certain letters.

Action Steps

Start with Writing

Get out some pen and paper and try this short writing exercise.

Set a timer for 5 minutes, and write about “I feel the best when…” or use this printable form to guide you.

Think about the things you do, people you see, places you go, things you smell/taste/touch, things you say, things you think and believe.

It’s normal for people to write that they feel best when they are resting – your challenge is to also find things that are pleasurable and interesting that are also active and with other people.

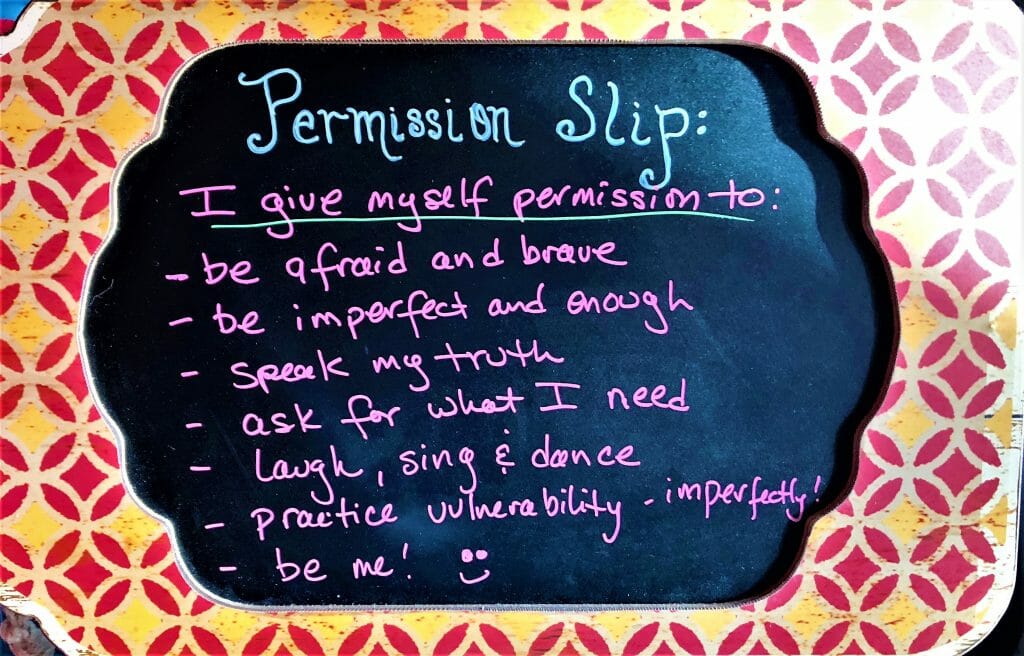

Permission Slips

The writing task above can help you to identify activities, people or places that help you feel good and experience fewer pain symptoms.

Now, use that to give yourself permission to do more of the things that help you to feel good, and have less pain.

Permission slips, as explained in this post from Linda Crawford can be post-its or small pieces of paper that help you to treat yourself kindly, and do the things that you need and want to do, without the guilt or shame that is sadly common when you’re focused on caring for yourself.

Make a plan and gather your supplies

Although distractions are going to encourage you to be more active, you also need to work out your starting point for the activities you choose.

- If you’re going to walk further or exercise more, how far or how long do you feel confident doing now?

- For sitting or standing, how long is comfortable now, on what chair or surface?

- Do you get fatigued or does your pain start creeping up after any length of time?

Don’t start by doing more activity than you’re currently comfortable doing, but increase the “feel good” and distraction factors first, then add more time or distance gradually.

If you need any new equipment, to co-ordinate with others, or find new music or funny videos, gather and organize what you need to help you succeed.

Remind yourself that your excellent alarm system doesn’t always require your attention. Have a few clever sayings that help you to remember the way that the danger/ safety balance works. Try these ones: “I am healthy, but hurting”, “flareups happen, don’t freak out”, – and go and seek some SIMs! (thanks to David Butler from NOI for these sayings)

Editor’s Note: Sometimes we share links to articles, products, or services which are not free. We make every effort to share resources which are easily available to everyone, and we do not make any money by sharing these types of links, even if you sign up.

Learn More

- “Knowing” about pain doesn’t mean you know how to apply it to yourself. This Physical Therapist who had to find her danger/ safety balance before she recovered from persisting pain.

- Get the Explain Pain: Protectormeter Handbook HERE

- Learn more about the Danger/ Safety Balance in Pain

- Try the BrainChanger app for finding and tracking your danger and safety levels.

Dr. Elliot Feldman is the Supervisor of the UW Medical Center Eastside Specialty Physical and Occupational Therapy Clinic.

He earned his Doctorate of Physical Therapy and Manual Therapy Certification at the University of St. Augustine in Florida in 2010.

His clinical and research expertise include chronic pain treatment utilizing modern pain neuroscience education and graded motor imagery, sports injury recovery and performance, bio-psycho-social treatment of spine conditions and direct access implementation.

Treating Pain with Kindness 3: The Power of Touch Treatment

Treating Pain with Kindness 3: The Power of Touch Treatment