If you are looking for information about back surgery, you’ve probably had back pain for some time, and this pain is badly affecting your ability to live life as you choose.

Your search for surgery information might be coming from the common thinking in conventional health care circles that surgery is the “final fix” for back pain. Surgery is usually considered after other treatments have failed to relieve your symptoms, so that you can return to your normal life without pain.

It is helpful for you to know some of the truths about back surgery, so that you can approach a possible procedure with good information and your eyes wide open to some of the misconceptions about it.

There’s a greater chance of a poor outcome with surgery if you have significant, long-term back pain – especially if you haven’t learned about pain and the many reasons why it can persist.

Understanding pain helps improve your odds of a successful surgery and recovering well, or choosing not to have surgery until you have worked through some of the non-structural causes for persisting spinal pain.

Let’s take a good look at the expectations people have of surgery, risk factors for poor outcomes, when surgery can be successful, and when to get a second opinion about your surgical options.

How Did Surgeons Get It So Wrong?

The spine surgery industry is out of control. I am not against surgery, and I was a complex spinal surgeon for 32 years. From the beginning of my career, I felt that too much surgery was being performed. However, for almost eight years I was a part of this aggressive surgical approach.

I was under the impression that the success rate for a fusion for LBP was over 90%. Otherwise, why undergo such an invasive procedure?

I was shocked when a research paper came out in 1993 showing the return-to-work rate was only 22% after a low back fusion for pain. I immediately stopped performing that operation after learning about those results. If that procedure was a drug, it would never be approved – it doesn’t even reach a “better than placebo” level of effectiveness. Twenty-five years later, there is still no research that supports this operation.

I didn’t have any alternative treatments to offer and I was sliding into my own “abyss” of chronic pain from which I didn’t emerge until 2003. My recovery from persisting pain seemed accidental at the time, but the process that worked for me turned out to be supported by research.

The last ten years of neuroscience research has revealed the nature of chronic pain along with the solutions. I have now witnessed hundreds of patients become free from the grip of chronic pain; most of them without any surgery.

Much of the problem with how we treat back pain comes from the misunderstanding about what pain is, and why it occurs.

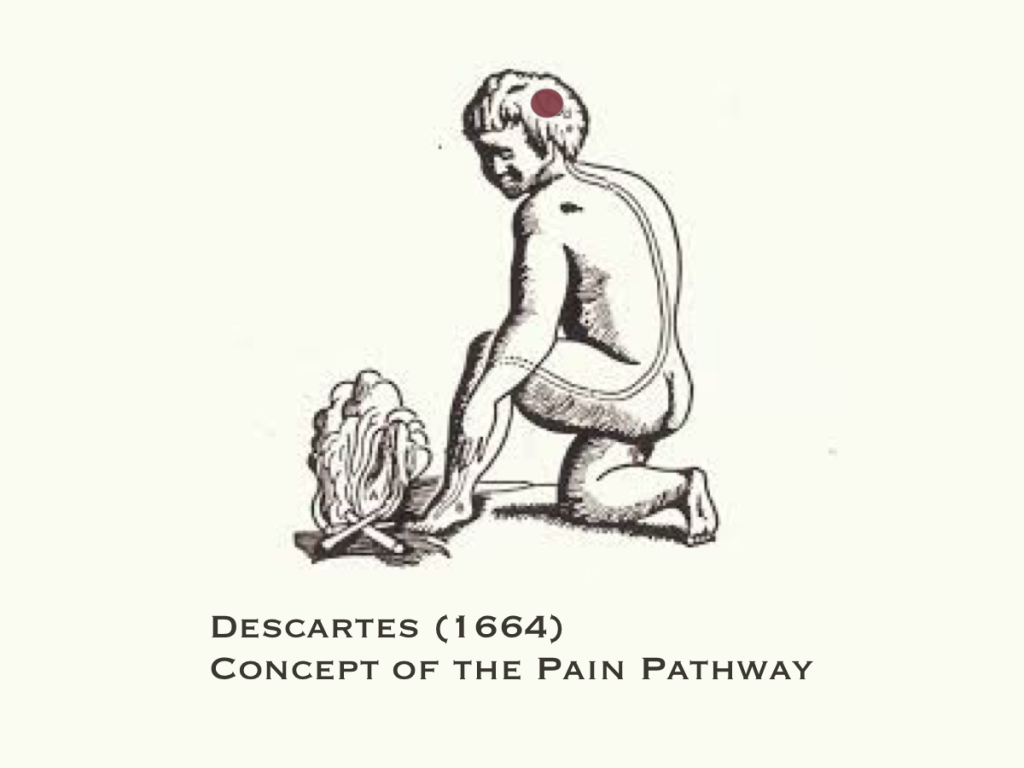

Much of the blame sits with the 17th-century philosopher, Rene Descartes. Descartes’ theories clearly separated mind and body, and they were innovative ideas in their day. The problem is that modern science tells us that the mind and body work together in complex ways to create pain, as a predictive alarm not as a damage detector.

Pain doesn’t work the way that Descartes’ diagram above suggests. There are no pain fibers or pain pathways that alert the brain. Only “danger” pathways – which the brain has to weigh up and decide if you need to feel an alarm – pain.

Descartes’ picture seems to make sense, because pain feels like it’s happening only in your body. There are many other complex processes that occur in other body systems that determine whether or not you’ll feel pain, even if you have damage to your tissues.

As a surgeon, I was taught to have all the answers and to be able to “fix” problems. Modern pain science calls into question the problems that we think we need to fix.

I don’t think surgeons are setting out to harm or profit from spinal surgery. They are continuing to use the information they have learned and practiced, based on the structure-based training received in medical school.

Treating pain well is not like taking your car to the shop for a repair and expecting the same percentage of success that you would with your car. Nothing in the mechanical world resembles the intelligent complexity of pain. We are wrongly using a structural approach for a neurological process.

Spinal Surgery Doesn’t Cure Low Back Pain ( and it Damages Healthy Spines)

Over the last five years, I have witnessed people undergoing increasingly major surgeries for pain that don’t have clear indications for surgery. In fact, many patients have procedures on spines for normal age-related changes. Successful spinal surgery requires something for me to “fix”, and if I can’t see it on an MRI, there’s not a structural problem that I should be trying to fix.

The problem with these painful, but non-damaged backs receiving surgery was that they consistently had much worse pain and disability after the surgery, than they did before. With another level of hope gone, people often become even more discouraged.

Seemingly obvious spinal problems, like disc degeneration, bulging, or rupture, or joint changes, have been documented to be normal age-related findings. They are not the likely source of back pain.

If a nerve is pinched with corresponding leg pain, then that is potentially a surgically correctable problem. Back surgery doesn’t solve back pain. Yet tens of thousands of these surgeries are still being performed without good clinical indications to do so.

Any spine surgery creates permanent changes to the shape and mobility of the spinal column and the bigger the operation, the more potential there is for ongoing problems due to greater changes. The frustration of patients being made worse by failed back surgery is beyond words, and there is no turning back.

Deciding to Have Spinal Surgery

Spinal surgery, like other branches of surgery, is excellent at correcting abnormalities and symptomatic structural faults in your body. The right surgery, on the right patient, can have positive and life-changing results.

Surgery is most likely to have good outcomes if you have a well-defined anatomic problem with your spine, that matches up with your symptoms and where you are feeling pain.

There are better chances that your surgery will be a success if:

– your pain is reliably located in one area of your body, with a consistent pattern of referred pain in your arm or leg.

– your anatomical changes can be seen on an MRI, and the changes match the known referral patterns of pain for that spinal level.

– you have done a comprehensive mind-body rehabilitation program that improved your mood and back pain, but your leg symptoms are persistent.

If your pain is in a broad area of your body, it moves around and isn’t well localized to one place, and there are no significant changes on an MRI, then the chance of successfully relieving your pain with surgery is low. There is a 30-60% chance of making it worse if you haven’t addressed the factors causing your chronic pain.

If the description above is how your pain feels, it’s critically important that you know that surgery is not an option for you. Fortunately, as you systematically address all the components of your pain, it will reliably decrease or disappear. This is the gift of modern neuroscience.

Getting a Second Opinion on Spinal Surgery

Before you commit to having surgery, you need to feel confident that what can be seen is highly likely to be causing your symptoms, and that an operation to correct the changes seen on a scan or x-ray will result in a significant symptom change.

You need get answers to these 4 questions:

1. Do the changes to my spine on MRI match the symptoms I have?

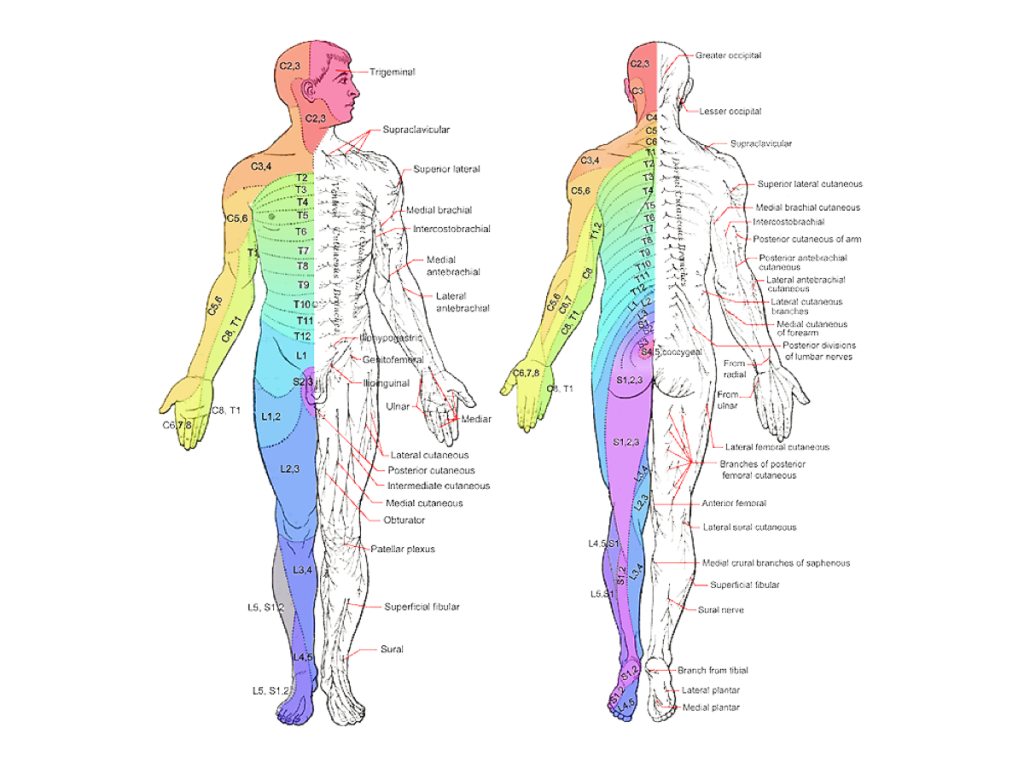

Your surgeon can show you how the findings seen on your MRI, such as disc changes, are causing symptoms in the corresponding areas of referred pain and nerve distribution.

2. Does research show that the planned surgery has high success rates for my specific condition?

If you have a disc bulge somewhere in your spine (and most people do), it is not causing your back pain. If it’s causing nerve compression, it will cause specific pain or weakness in your arm or leg, and these need to be carefully matched up.

The decision to have spinal surgery is massive and can be life-changing. First of all, never make a decision on elective spine surgery on the first visit. If you feel pressured to do so, find another surgeon.

Your surgeon needs to be up to date on the evidence and research for the surgery that is being proposed. They need to be able to explain why it is the best option for you and explain the procedure clearly.

3. Have I done a comprehensive pre-surgery “prehab” program?

If surgery is the best option for you, then both your body and your mind need to be well prepared. Starting movement and exercise after surgery is too late! The steps outlined in the “Action Steps” section are part of what many of us are calling “prehabilitation”.

Your levels of fitness, mobility, anxiety and sleep quality will all affect how you recover from any surgery, and getting them under control beforehand could give you the option to avoid surgery altogether.

Only a small percentage of surgeons are addressing the known risk factors that adversely affect outcomes before recommending surgery. We work on these factors for at least 8-12 weeks before undergoing surgery. Many patients with surgical lesions cancel surgery because the pain disappears. This has been somewhat surprising. Those patients who do go ahead with surgery after being well-prepped consistently do well.

4. How stressed and sensitive is my nervous system?

This question takes some personal reflection and perhaps asking the people around you for their perspective too. How much stress is there in your life, and how is it affecting you? How much anxiety do you have, and do you always feel like you’re on “high alert”?

A stressed nervous system is a sensitive nervous system. A sensitive system has the potential to increase pain, and also influence other protective systems like your immune and endocrine systems. Changing a sensitive nervous system isn’t difficult once you understand the process, but it certainly doesn’t happen in the surgical suite.

Successful Spinal Surgery

If you have a non-stressed nervous system with clear anatomical changes that plausibly explain your symptoms, then you could be a good candidate for surgery if you feel your pain is severe enough to warrant the risk of surgery.

Even the simplest operations can go awry. No one thinks they will be the one to have a complication. If you have a highly stressed nervous system, without anatomical changes, the chances of surgery being helpful and effective for you is small, and there is a significant chance of having worse pain after surgery.

Action Steps:

- Are you managing stress and anxiety?

“Stress” is a catch-all term used for the feelings of arousal and stimulus that come with staying safe in a world full of threats.

The threats that you face in a modern world still affect your body in the same way as being cornered by a wild animal that wants to eat you.

Unlike our primitive environment, where you get eaten or you escape, the” wild animals” you face in a modern world are constantly stimulating our protective senses. Financial stress, work pressures, relationship problems, loneliness and disconnection are only some of the stresses that we face every day. Pain is additional particularly unpleasant stress.

The effects of stress are physical. You feel stress in your body – your heart races and your breathing is fast and shallow, you feel jittery and unsettled, your muscles tense and get ready for action. Even when you’re just sitting at your desk. This chemical cocktail created by stress sensitizes nerves, and affects how well you heal from any injury (such as surgery).

If stress, anxiety, and depression are significantly affecting you, reaching out for professional help, starting self-care strategies like reflective writing and creative expression and finding ways to calm your nervous system are essential steps to recovering from persisting pain.

Read More:

A Guide to Managing Pain and Anxiety

- Are you getting good sleep?

It is difficult to make positive lifestyle changes without a chance to rest and to get a full night’s sleep. Most people with ongoing pain have disturbed sleep in some way, either as a result of pain, or from long-standing sleeping problems.

Sleep hygiene strategies, like limiting caffeine, establishing a calming bedtime routine, having standard sleep and wake times, and calming visualizations for sleep are all useful strategies.

If your sleep is severely disturbed, by pain or by other factors, you may talk to your doctor about options for short-term sleep medication to help break the exhaustion cycle that comes with poor sleep.

Read More:

- Are you getting enough movement and exercise?

You have probably heard from health professionals that increasing movement and exercise is an essential part of recovering from persisting pain.

It may also sound contradictory, as many people find that exercise can increase their pain, however there are ways to make increased activity work for everyone.

If you’re a candidate for surgery, you cannot wait until after surgery to make a start.

Any movement or any activity that is off the sofa or out of bed is a good start. Understanding that pain is not a sign of damage is important – you need to know that you’re safe to make small increases in your everyday movement, no matter where you’re starting from.

Small, gradual progressions in the time you spend moving every day is something you can do without needing professional assistance. Gentle exercise like walking has been shown to be just as effective as specific exercise programs, particularly in the early stages of increasing exercise.

If after reading this blog you’ve got doubts about surgery, now is the time to start asking more questions of your healthcare professionals.

These questions will help you to decide whether your planned surgery is something that you can feel confident having now, whether there are changes you need to make to have your surgery with more confidence in the future, or help you seek out new ways to treat pain that is not suitable for surgical intervention.

Dr David Hanscom is publishing a new book in Spring 2019, called “Do You Really Need Spine Surgery: Take Control with Advice from a Surgeon”. If you’d like to pre-order his book to get an expanded version of these concepts, CLICK HERE.

Dr. David Hanscom is a spinal surgeon on a mission for change. As a board certified orthopedic surgeon, David specializes in the surgical correction of complex spine problems. Despite a very successful career as a surgeon, David noticed there were many people that had pain that did not need his expertise with the scalpel. This has led David to write the popular Back in Control blog and book, and develop effective non-surgical treatment methods for back pain.

Use the Positive Power of Distraction for Pain Care

Use the Positive Power of Distraction for Pain Care

Hi I hurt my right side lower back and I thought at the time and was told it was a lower back strain… I kept working as a dump truck operator for a couple of months, until the pain was excruciating!! I had an MRI and it confirmed I had a L5/S1 cracked bulged disk! Is it common for this type of injury to get worse over time resulting in disk being cracked/ bulged, right side sciatica and loss of sensation of my right foot and unable to work due to pain???

Hi Fiona – thanks for your comment and question. Disc and nerve pain is something that needs smart therapy and good information. Learning about how discs do heal, how nerves change their sensitivity and how to get back to moving again are all good for your ability to recover. Some people do have surgery, but it’s not the only thing that helps this condition, nor does it guarantee a positive outcome. Allowing time to heal and adapt, support to get back to normal activities and making the adjustments to work and life that help you stay connected to “normality”as much as you can are the best things to work out – before any talk of surgery for disc-related leg pain.

REally? Pain is not a sign of damage. I developed the most excrutiating pain last week, in my left buttocks, left hip and radiating down the outside of my calf sometimes into the foot. I could hardly walk or stand up straight until I got pain meds. My MRI shows foraminal stenosis L5-S1 due to arthritis and significant scoliosis. Isn’t this damage to the foramen, and also a pinched nerve. I have most of the other things under control. I meditate for 10 minutes almost daily. I was exercising 1 hour 3-4 times a week until this pain occurred. It seems like opening up the foramen would be good surgery. what are the downsides?

Hi Sharon, surgery can be something that’s lifechanging but very often, it isn’t. Changes seen on scans and x-rays are not to be ignored, but often they don’t tell the full story of pain, and of possible recovery without surgery. Many people can return to living full and active lives, without significant symptoms, without surgery, but every decision must be made on a case-by-case basis. You might find more information on surgery and alternatives on Dr Hanscom’s website http://www.backincontrol.com